Advent Unlimited (Page Two)

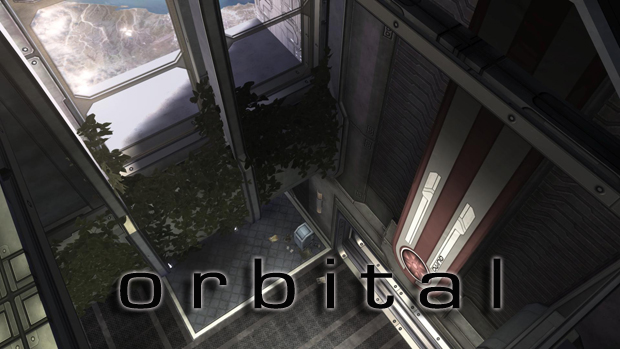

This map’s fiction takes place at the zenith of one of Halo’s iconic space tether locations: the Quito Station, which is located high above Ecuador. It is essentially a series of steel-gray commuter hallways, loading bays and maintenance corridors extended well above the brilliantly white hue of Earth’s curved horizon line. The map has been described a number of ways already, but because of its complex nature, most verbal portraits and horseshoe analogies have fallen short of effectively articulating it — and what follows may be no different.

To be simple, imagine two bases on either side of a map. Imagine that both of these bases have two garage doors each. Now imagine that what connects the two bases are a pair of tunnel corridors, but instead of strictly linear connections, one base’s top garage connects with the other bases’ bottom one, and vice versa. If you were to now take these bases (instead of across from each other) and put them side-by-side on separate floors, you’d have Orbital.

That help you? Probably not. To be honest, Orbital is probably the most difficult multiplayer environment to explain in the last two titles — trying to understand it by doing anything short of exploring the environment on your own is likely to become an effort in futility. But despite its steep learning curve, the real question remains: Is the map any good?

Certainly the environment looks gorgeous, its vibrant color palette tinged here and there throughout the crate-packed hallways. Its atmosphere alone is impressive to say the least: hanging gardens in ornate commuter loading rooms, audible instructions being offered by the station’s operator, a floor-engraved memorial recognizing the civil engineers responsible for the tether’s design and windows which peer out onto South America’s beautiful coastline far below. Perhaps the most emphatic decoration of Orbital is the commemorative wall monument in each of the station’s two stairways, honoring the creators of the Shaw-Fujikawa Translight Engine.

Tobias Fleming Shaw and Wallace Fujikawa were responsible for Slipspace travel in Halo universe and their memory is not lost on the walls of Quito Station.

And all of this is fine and good, but if the map doesn’t play well then it is all for naught.

Although its long term sustainability remains uncertain, it can be said with some measure of certainty that Orbital is a blast given the proper context. Like most maps, the best way to leverage fun out of them is to find the two or three gametypes which work the best. This map has been billed as an asymmetrical one-side objective environment, but interestingly enough, the map plays very well with symmetrical and neutral gametypes. There is enough symmetry offered by the bases’ general layout and the factors involved in moving from one to the next for it to have the functionality of a dual-sided map.

At one end of Orbital lies the bases, red base above leering down into blue base below — a division of glass in between both teams at the start of the match. The pair of aforementioned tunnels shoot off to the far side of the map before returning to the opposite base it left from — with a sniper rifle supplying the power weapon for the bottom floor and the rocket launcher for the top. Both are found adjacent to a deadly pit, at a vicious choke point on the furthest end of the map.

The most popular choke point on Orbital is the rocket spawn, which is located in between the civil engineer memorial and a window peering out on South America hundreds of miles below.

The bases themselves are somewhat familiar to the ones in Terminal’s offensive base, with its dual floors and multiple ramps, but ultimately they are their own breed. By default, two Mongooses occupy each and during one-sided objective gametypes, the offense is given a death-dealing Ghost to make up for the bases’ potent defensive geometry — only one of the main doors is open, the other needing to be triggered by an adjacent keypad. A secret entrance can also be found to the upper levels in a hidden side door near the outside of each base.

By default, Team Slayer and SWAT components will feel most natural, not too unlike they did on Elongation, Orbital’s older brother. They work well and in many ways force choke point battles more effectively than any other Halo map prior. This inevitable design niche allows players ample opportunities to recognize and enact ambush scenarios on their foes. For example, once you’ve learned the layout of the map you can watch your allies in distant firefights, accurately determining where the enemy has come from and where they are moving to. From that information, you can properly set up shop to get the drop on them, by either cutting them off at a pass or lying in wait around the corner or crate.

This alone makes the map gratifying on a lot of levels. So, despite what you may have heard from others about Orbital’s design, once it is learned, the map has an aggressively interesting take on Halo combat — not only is it a looker, but it works as well.